Abstract

Relapsing and refractory acute myeloid leukemia (AML) is responsible for dismal outcomes in both pediatric and adult patients. However, we (Bolouri, Farrar, Triche, Reis et al, Nature Medicine 2018) and others have demonstrated that the mutational burden of AML in children is remarkably different from that in adults. Gene fusions (such as those involving KMT2A/MLL or NUP98) are responsible for many primary refractory cases in children, while point mutations (such as those involving DNMT3A or TP53) commonly associated with refractory disease in adults are absent from children. Thus it appears that the evolutionary dynamics leading to presentation are age-specific, favoring highly penetrant structural variants in younger patients, while older patients more often present with mutations that confer stress resistance to mutant progenitors.

By contrast, when we analyzed a clincally well-annotated cohort of relapsing and refractory pediatric AML patients alongside a similarly curated adult cohort (from Li & Garrett-Bakelman, Nature Medicine 2018), we observed that certain recurrent mutations (FLT3-ITD, FLT3-TKD, WT1 framshift or point mutations) are enriched in both adults and children who fail treatment, and variants in these genes tend to exhibit increasing variant allele frequencies at relapse. Revisiting two independent cohorts, one published (Klco et al, JAMA 2015) and one unpublished (Malek et al, unpublished) studies, we verified that FLT3-ITD, STAG2, WT1, and TP53 mutations associate with, and expand in, secondary refractory disease at all ages.

More startling was our finding of recurrent epigenetic silencing in children with AML not only at presentation, but also (in specific focal cases) at relapse and induction failure. Here again we observed concordant promoter hypermethylation, increasing in both frequency and magnitude, at specific loci in both adult and pediatric cases across independent cohorts. HES4, ZNF229, and in particular the activating NK cell ligand ULBP1 appear to be selectively repressed in an expanding population of clones at relapse.

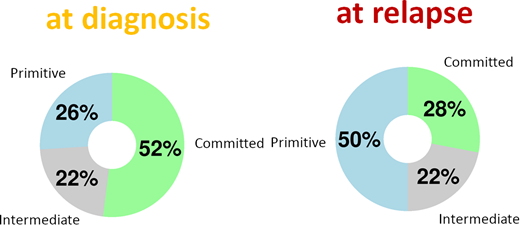

Furthermore, after correcting for differences in blast count (purity) and inter-individual differences, we nonetheless find that the genome-wide DNA methylation profiles of relapsing cases resemble primitive hematopoietic stem cells relative to more committed myeloid (or, in rare cases, lymphoid) progenitors. This shift is particularly notable for its consistency: in any given patient, a supervised embedding of their leukemic cells' methylome at relapse will almost always appear to be more primitive than at diagnosis.

Based on these and other observations, we propose that metabolic adaptations and convergent selective pressures during and after standard treatment drive both adaptation and resistance. The sites most frequently hypermethylated in both relapsing and refractory cases are enriched for EZH2 binding sites and decrease in methylation with 5-aza-CdR treatment, suggesting one possible alternative treatment in these cases.

No relevant conflicts of interest to declare.

Author notes

Asterisk with author names denotes non-ASH members.